A. Gregor

– PROBLEMATIC EXPERIENCE: RECOGNITION, REFLECTION, RESPONSIBILITY IN ART

It's remarkable that our experience of the world, which includes our recognition of and response to things in it, is so often unremarkable—that is, until we are faced with something we don't recognize or aren't sure how to respond to. Only in the latter case, when a problem arises, do we begin to reflect on the generally unproblematic quality of experience, to wonder how such problems arise and how they might be resolved when they do. And so we are faced with a problem: a problem about problems that I’m inclined to resolve by making a distinction within our experience of the world, by slicing experience as a whole into two faculties so that experience is unproblematic—we might say ‘normal’—when these faculties are in harmony but problematic when in discord: the faculty of conceptualization, which organizes particular perceptions under abstract concepts already held; and the faculty of perception, which apprehends sensory data, presenting it to conceptualization for organization, or, if no appropriate concept exists, assists in creating a new one. By drawing this line between the faculties of conceptualization and perception and their corresponding objects, concepts and perceptions, we can account for the potentially problematic nature of experience by positing that within experience abstract concepts and particular perceptions are reciprocally related by their corresponding faculties and thus can fall in and out of harmony, so that, when they are out of harmony, a problem arises in experience that wants resolution; that is, that we, the experiencers, want to resolve.

If you’ll accept this distinction as our starting point, we can generate from it a structure that conceptualizes four ways these two aspects of experience might be related: (1) concepts and perception may be in harmony and thus experience unproblematic; (2) a problem may arise in experience wherein concepts are inadequate to organize perception, so that either old concepts must be wholly abandoned and new concepts created to achieve resolution or (3) concepts broadened in order to subsume incongruous perception; or (4) perception may deny conceptualization while concepts insist on organizing them. According to this schema, it’s only in the first scenario that a problem doesn’t arise. In the second and third scenarios, problems arise in experience that can be resolved. In the fourth, experience is irretrievably divided so that resolution can only be achieved by successfully ignoring the problem.

This schema we’ve generated from our initial distinction presupposes that perception can’t occur without concepts. These concepts may be innate, arrived at inductively, inherited, or created. Regardless of how we come to hold them, we can say that the aggregate of our concepts compose our world, or conceptualization of it. Together concepts paint a picture of the world as one sees it, a worldview, in light of which one recognizes and reacts, consciously or unconsciously, at any given moment. This worldview is the structure through which experience is understandable; is where we stand, a way of seeing, a vocabulary and grammar that describes this world, a limit to what is conceivable, what is realizable; is the world that we perceive. Perceptions are presentations of that conceptual world in its particularity, particular instances of abstract concepts, which can be, and often are, harmonious with one’s conceptual structure. But perceptions can also be inarticulable in a given vocabulary and can push, perhaps even puncture, the limits of what is conceivable, can change our way of seeing, which is to change our world. It is tempting, perhaps inevitably so, to believe one’s own worldview to be an accurate picture of the world as it really is, as if the world were an object we could come to understand through empirical observation, as through the lens of a camera, microscope or unbiased eye. But the world is conceptualized differently by different people, their actions and products not mere objects that can be known empirically but expressions of their subjective worldview. The world we perceive is composed of the worldviews of others, at least in part. How we resolve a problem between our conception of the world and our perception of others’ worldviews—that is, between our concepts and our perception of the concepts of others—is a question, not of coming to know the objective world merely, but of coming to see another’s conception of that world and consequently relating theirs to our own. It is a problem of recognizing, reflecting on and responding to another’s worldview. If we emphasize the recognition, we might call such problems that arise in experience epistemological; if we emphasize the responsibility, moral. I am going to emphasize reflection and call them aesthetic problems.

Art occasions relations between the viewer’s conceptualization of the world and their perception of the artist’s conceptualization of the world as embodied in the artwork—relations parallel to those between perception and concepts sketched above: (1) the viewer may find that they share a world with the artwork; (2) they may find such difference between their worlds that the viewer can only enter the artwork’s by abandoning their own; (3) the viewer may expand their conceptual world in order to assimilate the artwork’s to it; or (4) the viewer may insist on using the concepts of their world to understand the artist’s while finding reconciliation to ultimately be impossible, which may result in preoccupation with the problem it presents to them or in walking away from it, perhaps to look at a more pleasing painting. This parallel we’ve set up between the relation of concepts and perception in our experience of the world and our experience of art suggests that reflecting on how we resolve the problems that arise in artistic experience, which artificially affords us reflection independent of recognition and responsibility as is demanded in our experience of the world, might prepare us to better recognize and respond when our world, or the interrelation of our world with others’, becomes problematic. To do so, let’s imagine four types of artwork that correspond to our schema. I will restrict the instances of each to painting, for painting, which addresses itself to the eye, is especially suited to problematize how we see the world. Paintings show us that others see the world differently than we do, so that we might see, or try to see the world differently, a different world.

Paint’s potential to mimic the appearance of different materials, textures, volumes and atmospheres can produce paintings that reinforce a worldview in which vision is a neutral means of coming to know an objective world, wherein perception is unproblematic because it seems to transmit to us a conception of the world as it really is. Such paintings don’t problematize the relation between the viewer’s conceptual world and their perception of the painting, but rather claim to represent the world accurately, as if through a pane of glass. I will call this first type of painting ‘descriptive painting’ because such a painting claims to describe the world as it is. A descriptive painting assumes congruence between the view of the world it presents—how it is perceived by the viewer—and the viewer’s conceptualization of the world, thus situating itself as an extension of the viewer’s world. The viewer’s concepts, and therefore their way of seeing and the vocabulary they use to describe what they see, are adequate to it already, so the relation between their concepts and their perception of the painting is unproblematic. Let’s look at Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps as a particular instance of our concept of descriptive painting. With imperceptible brushstrokes, naturalistic modeling and atmospheric perspective, the material properties of paint—its viscosity, color, handling—are made invisible, transformed into the material properties of other objects. Indeed, the painting announces itself as a window into a world not of paint but of familiar objects made from identifiable materials: flesh, leather, iron, stone. It presents a world that appears to behave according to the same laws that a viewer, who believes their eyes accurately tell of a world characterized by extension and material differentiation, expects the world to behave according to, and manipulates this expectation for a rhetorical end. Napoleon, with flesh so convincing it seems it might yield to touch, is painted wearing ornate clothing, pointing forward and upward astride a rearing horse, in the process of traversing the mountains with an army in the background. The horse’s glistening eyes seem to roll and its tensed muscles to twitch under its coat as its power is restrained by Napoleon’s utter control. Paint is manipulated to imitate the appearance of things as one who believes vision to record the effects of natural laws would expect. The painting is continuous with their conceptual world and by means of this continuity of concepts constructs a visual enthymeme that can be articulated as follows: Great paintings mimic the visual effects caused by natural laws; Napoleon appears, as if he himself were before our eyes, valiantly leading his troops over the rocky Alps whereon his name is carved alongside, and larger than, the names of great leaders throughout history; therefore, tracing the causal chain backwards, Napoleon is by natural law a great leader (and David a great painter). By stylistically establishing a world continuous with the viewer’s own, to which their way of seeing, and thus their vocabulary, is already adequate, and organizing that shared vocabulary into an argument, the painting claims to describe the world as ordered by natural laws and the qualities of the things in it. In this painting, description is used to the rhetorical end of persuading the viewer that, just as surely as they can see the clouds in the sky or the mountains on the horizon, they see their emperor is a great man.

But paint, in addition to being able to mimic the material properties of objects seen in the world, has material properties of its own, which can be used to make explicit the potential gap between concepts and perception. A second type of painting does the opposite of descriptive painting by restricting itself to the material properties of its medium, thereby creating a world of paint all its own. I will refer to this conceptualization of painting as ‘autonomous painting’ because such a painting creates its own vocabulary and uses it to define itself. In relation to an autonomous painting, the viewer must be born again into this new world by abandoning their normal way of seeing in order to form new concepts in light of the painting’s internal logic, the laws natural to paint. The relation between the viewer’s concepts and perception is problematic because an autonomous painting demands that it is like nature itself, absolute creator of new forms, and the viewer that clings to concepts external to the work, thereby failing to adapt to this nature, is a lifeform not long for the painting’s world. Mark Rothko’s No. 13 (White, Red on Yellow) is a particular instance of autonomous painting. No. 13, indifferent to the normal concepts of the viewer, announces itself to be a world of its own: it is large and so fills the viewer’s field of vision that it seems to engulf them like an environment; it is always changing because staring at saturated pigment creates after-images of complimentary colors that move as the viewer’s eyes move, thereby modulating the appearance of the pigment applied to the canvas; furthermore, like nature, it seems less to be something made by a human than something that simply is because its history is unknowable insofar as the process by which it is made obscures that very process. Once the viewer relinquishes their usual concepts—that is, leaves their world behind—and allows theirself to enter this new world that is the painting, they must let their perceptions teach them the concepts this world demands. Starting with all they have—what they can perceive—they begin to build new concepts: they see the shape of the canvas, the occasional glob of paint or brush bristle left behind, the relative effects of color—and, in looking, they realize that these perceptions occasioned by the painting are themselves mimicked in the painting: the shape of the large canvas is represented by smaller rectangles within; the physiological effect of the viewer’s eye layering after-images of color over the painting is reproduced by the material layering of paint on the canvas; the physical qualities of the materials, such as shadows cast by globs of paint, are reproduced in paint, as by a dark dot on its surface. By representing in paint the perceptions its own paint occasions in the viewer, the painting shows the viewer the concepts appropriate to its world: concepts of, what we might call, ‘rectangle,’ ‘layering,’ ‘paint glob;’ that is, concepts that grow out of the material nature of its medium. But we need not call them by these words; we could just as easily gesture or make up new words for our perceptions and the new concepts we abstract from them because the painting presents what it represents and represents what it presents. To enter this world of paint, the viewer must become a child again and through their sense of sight begin to learn a new conceptual structure, a new language, a new world.

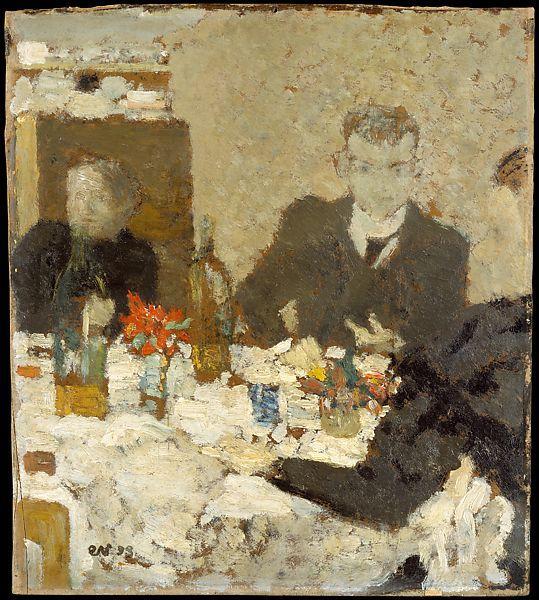

Taking advantage of paint’s material potentials for both mimesis and abstraction, a third type of painting depends on the viewer’s concepts to make intelligible what are initially unintelligible aspects of its appearance by problematizing the relation between concepts and perception in such a way that the viewer’s perception of the painting is close enough to, but different enough from, their conception of the world that the relation between concept and perception is problematic, but ultimately reconcilable. I will call these paintings ‘correlative paintings’ because bringing concept and perception into harmony requires the mutual adjustment—the co-relation—of both: the expansion of concepts to include novel perceptions and the conformation of novel perceptions to fit within those concepts. For instance, Edouard Vuillard’s At Table. Painted with a narrow spectrum of values and hues, the grayish brownish daubs of paint, made by a hand in motion that discovers the form its subject matter will take as it moves, assert that they are indeed paint applied to a surface while also representing, miraculously, a scene of people at a table. That the viewer perceives those patches of paint both to be paint and to be a table with three figures shows how concepts can expand to include perceptions and, conversely, how perceptions can be informed by those concepts in order to assimilate those daubs of paint to conceptual categories common to a domestic scene. Take, for example, the hand belonging to the figure at the right of the canvas, which, at first, may not be intelligible as a hand at all: in color, paint application and form the hand is nearly identical to the tablecloth that surrounds it, lacking any outline to delineate it from its background,—and yet, it is a hand.

Some combination of direction of brushstrokes and vicinity to a black silhouette suggests the viewer’s concept of ‘hand,’ while in relation to the suggestion of the concept of ‘hand,’ the paint daubs appear more hand-like than they may have at first. By correlating Vuillard’s paint daubs with the viewer’s concept of ‘hand,’ and vice versa, an equilibrium is reached between concept and perception: the problem of what type of thing the paint daubs represent is resolved. The painting’s patchwork of brushstrokes together with the viewer’s conceptual categories knit a harmonious scene populated by human bodies, lace tablecloths, flowers and glass bottles. But—and here is where correlative paintings, as exemplified by Vuillard’s At Table, differ from descriptive paintings like David’s Napoleon—in a correlative painting, the viewer must, at the same time that they see lace and flowers, also see the lace and flowers to be paint. The perception of paint and the recognition of a concept are inextricably interrelated. At Table doesn’t claim to describe a hand in the way David’s painting claims to describe the flesh and bone that compose Napoleon’s right hand. Rather, Vuillard’s painting uses paint’s materiality to occasion the recognition of painted things that appear very different from instances of those things as they are normally perceived in the world, showing forth the potential rift between our abstract concepts of a type of thing and our particular perception of an instance of a thing while occasioning the resolution of this rift by broadening our concepts to subsume the particular, albeit painted, instance.

Finally, there is a fourth type of painting, which also occasions in the viewer a feeling that there is a problem between concept and perception, but insists that the relation between the two is not so reconcilable as correlative paintings suggest. Instead, for this last type of painting, the relation of concept to perception is one of continual severing and suturing, slicing and stitching: a problem without harmonious resolution. I will call this type of painting ‘ambivalent painting,’ in the sense of showing simultaneous and contradictory attitudes toward something, because it occasions a divided experience in which concept and perception are unavoidable but irreconcilable. The following two paintings by Philip Guston are such paintings. The experience they occasion is necessarily fragmented: concepts are always inadequate to wholly account for perceptions, but perceptions nonetheless appeal to concepts to be understood. No amount of suturing can return experience—that is, the world—to harmony: nevertheless, these paintings attempt to nail it back together. This type of painting, or rather, these paintings, throw the schema from which their type was derived into question because they problematize the very function of a schematic, or conceptual, understanding: can an abstract schema account for particular experience? Can a concept be adequate to particular perception? Despite the risk of denying its own schema’s validity, it is here, with these paintings and the problems they pose, that we will spend the rest of this essay because it is from here, in the problems that arise between our perception and concepts and between our concepts and perception of others’ concepts, that the schema came.

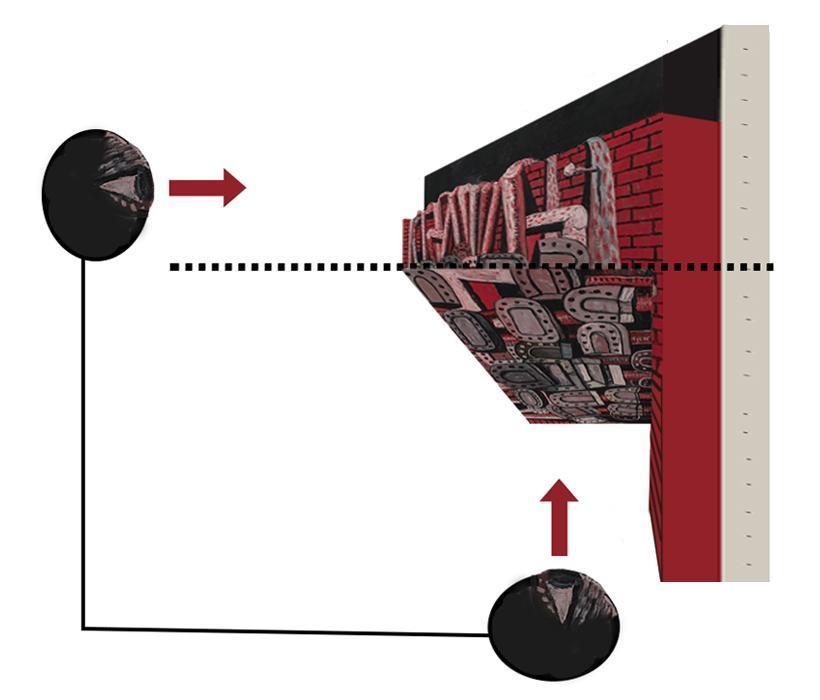

Let’s begin by describing Guston’s painterly vocabulary used in these paintings as it is perceived in Ancient Wall. First, a description of the types of things we recognize in the painting. In its top half the viewer perceives a black sky above a red brick wall, over which a mass of bare legs dangle, pink and knobby with dash-like hairs. The lower half of the painting is filled with a mass of diverse objects that can only hesitatingly call shoe soles, some connected to red stalks—bloody limbs?—that sprout from an area of black paint—perhaps a shadow?—at the bottom of the canvas. But this description, being verbal, emphasizes those things that are recognized, more or less, to belong to concepts continuous with our conceptualization of the world, concepts for which they have words: ‘sky,’ ‘brick,’ ‘wall,’ ‘leg,’ ‘shoe;’ whereas many other things in the painting, though they are perceived to be similar in form and paint application to these recognizable things, refuse to fit neatly into those same concepts,—or any concept, for that matter—so that we might hesitate to call the area of black paint a shadow, opting instead for ‘that shadow-like thing.’ Such a description that emphasizes words, or abstract concepts of things, can only be partial for a painting that is so emphatically paint. We must now turn to describe the same painting with emphasis, not on what types of things are recognizable, but the perception occasioned by the paint itself.

The painting is composed of marks from a painterly vocabulary of which the dash-like brushstroke made by a quarter inch flat brush is the smallest unit, as in the leg hairs; and from a limited vocabulary of colors—primarily red, black and white—employed separately and so mixed to make pinks and grays. The dashes, when placed end to end, form a ragged line or, when made with a large brush, compose the swathes of paint that cover the canvas. The ragged line sometimes functions as a contour that transforms a swathe of paint into a recognizable thing; sometimes that same ragged line is simply that, a painted line that can’t be seen to function as the contour of any particular thing, despite appearing formally indistinguishable from the aforementioned lines that bound something recognizable. In these latter cases, the line is an instance of a painterly vocabulary applied without representational function: paint perceived as paint in contrast to a painted instance of a recognizable concept. This double use of paint problematizes our attempt to assimilate our perception of paint to our concepts by employing a vocabulary of painted forms in two exclusive ways: on the one hand, the units of the vocabulary are composed so as to occasion the recognition of particular instances of types of things; on the other, the units are simply perceived to be paint applied to a canvas in an idiosyncratic manner.

This doubleness exemplified by Guston’s painterly vocabulary, in which the same brushstroke can be recognized to function in two different and contradictory ways—either representing a concept or simply presenting paint for perception—applies to Ancient Wall as a whole. The painting, like an image that occasions a gestalt shift, presents two views: two different paintings on a single canvas that represent two contradictory views of the same scene: the first, the view the painting presents to perception the second, a view that requires conceptual reorganization to see. The painting at first—the ‘first painting’—is perceived to be a landscape scene with a pile of shoes in the foreground, which takes up the bottom half of the canvas, in front of a brick wall with legs hanging over it in the background, which, with a black sky, takes up the top half of the canvas. An unsettling scene of limbs without bodies made more unsettling when we reflect on how we recognize these things to be limbs and shoes although they are unlike any limbs or shoes we, or at least I, have ever seen. We experience a problem of how to organize our perception of the painting so as to assimilate it to our worldview, subsume it under concepts already held. We can only continue to look, to perceive the painting more particularly, letting the faculties of conceptualization and perception wrestle. Eventually—in my case, hours later—a second way to see this painting, a ‘second painting,’ is perceived; or rather, conceptualized. To see this ‘second painting,’ the viewer must recognize in the ‘first painting’ instances of the concepts ‘leg,’ ‘foot,’ ‘shoe’ and ‘sole’ and subsume them under another more comprehensive concept: that of the body as a whole, in relation to which the concepts are parts that are, in the first painting, severed from one another. By conceiving of their potential continuity,—that in relation to a ‘body,’ a ‘leg’ is continuous with a ‘foot’ that is sometimes in a ‘shoe’ with a ‘sole’—we can conceptually reconnect the shoe soles in the foreground to the legs dangling over the wall behind by imaginatively flipping the bottom half of the canvas. Reorganized conceptually, the bottom half of the canvas becomes a view of the legs hanging over the wall seen from another perspective, from underneath, as if we each—I—could enter the scene in the first painting, lay on the ground with my head touching the brick wall to look up at the shoe soles of the shod feet connected to the dangling legs while simultaneously seeing the scene that I’ve entered in the top half of canvas. Now what appeared in the first painting to be a pile of shoes turns into a canopy of feet in the second, the black shadow-like-thing from which the feet were sprouting in the first transforms into the sky above the wall at the top of the canvas, the bloody limbs continuous with shoe soles flip to be the dangling legs reflecting the red light of the brick wall behind them. The single eye painted in the bottom right corner of the canvas confirms this view: a representation of the concept of vision separated from a body, suggesting another view from within the painting. A view that is impossible for me, who can’t physically enter the painting, to perceive, but is possible for me to conceptualize.

But this doesn’t resolve the problem. This second conceptual view can only be maintained by an act of mental gymnastics because it requires a reconceptualization of the painting that contradicts the perception of it. Our experience of the painting remains irresolvable because the single canvas contains within it two contradictory paintings: the first, perceived to be a unified view of a landscape with fragmented body parts in which the bottom and top halves are respectively foreground and background; the second, a fragmented view of a landscape with unified body parts, in which the top and the bottom halves must be conceptually reorganized so that the viewer simultaneously perceives a view of the scene looking at the canvas, as one looks at a scene from a window, and a view from within that scene, but perpendicular to it and from beneath. The painting as a whole occasions a problem in the viewer’s experience in which all the perceptual data can’t be subsumed under concepts, but neither can concepts be fully abandoned because some perceptions are indeed recognized as belonging to them: on the one hand, the viewer’s perception in which the landscape is unified required the fragmentation of their concept of body; on the other, the conceptualization that unifies the limbs into a whole body fragments the viewer’s perception from the conceptualized view. The painting(s) tempt(s) us to resolve this problem while symbolizing its impossibility in the two what I can only call ‘leg-like-things’ hanging over the wall on the right, deflated by nails: a means of uniting and puncturing, or uniting by puncturing. In the experience of this painting, the problem between concept and perception can only be resolved at the cost of one or the other. That is to say, it can’t be.

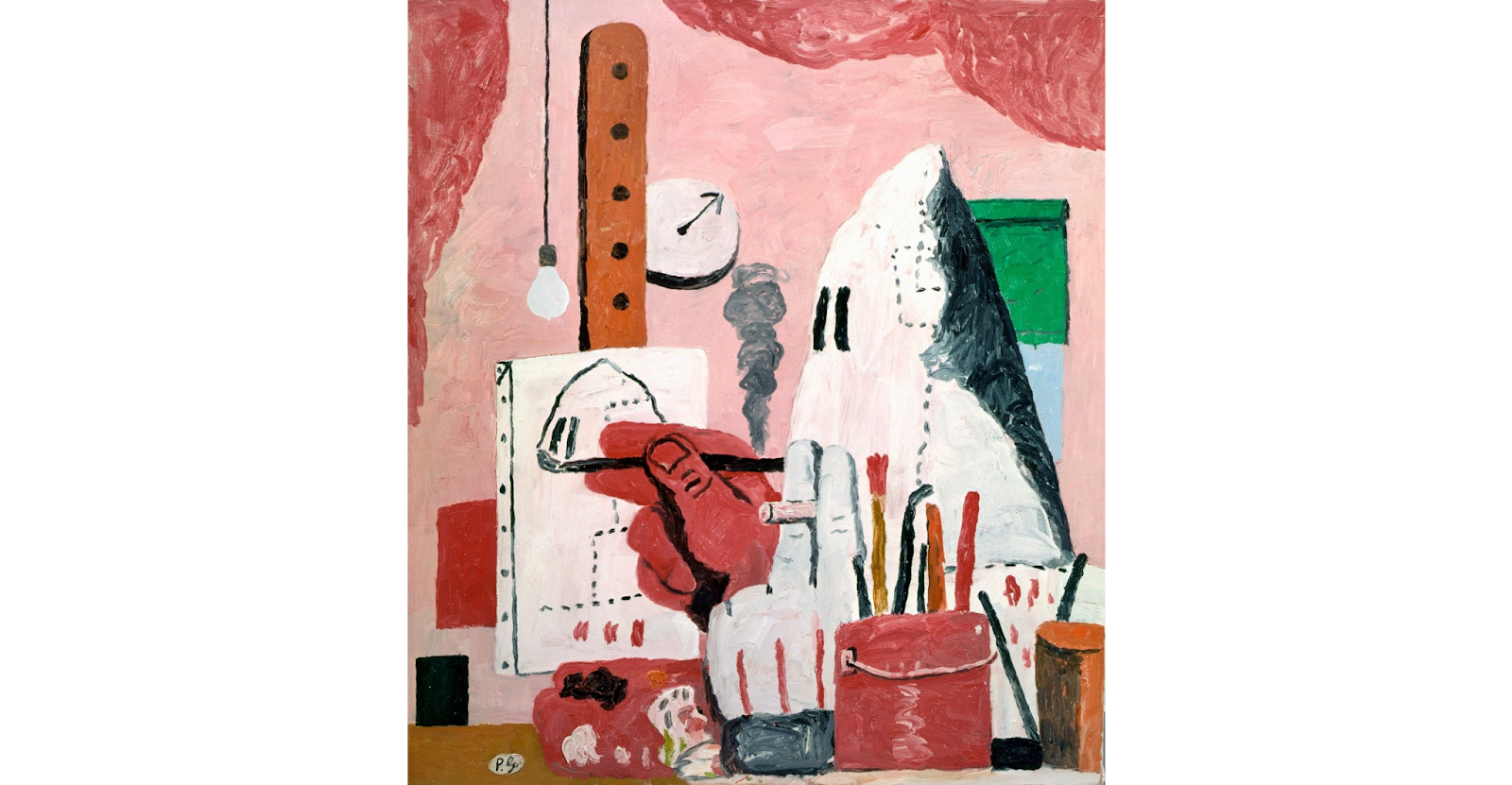

In looking at the problems that arise between concepts and perception in the double function of Guston’s painterly vocabulary in general and the double view in Ancient Wall, I’ve limited my analysis to problems that arise between the perception of paint and the recognition of the paint as a thing belonging to a concept that is in itself unproblematic. I’ve used the term ‘problematic’ to describe experience in which a problem arises and occasions reflection, in contrast to the contemporary moralizing usage of the term. However, this term is commonly used to describe statements or actions that pose moral problems, usually to condemn those statements or actions. Thus far, my reflections have emphasized the aesthetic, so I’ve used the first sense of the term because, as I said in the beginning, art seems to grant reflection a degree of autonomy from epistemological claims of truth and moral demands of responsibility, to create a space in which to work out problems without practical consequences. But some paintings make clear that this autonomy is indeed artificial; that aesthetic reflection rubs up against moral responsibility, just as it rubs up against the epistemological problem of recognizing abstract concepts in particular perception. With this moral sense of problematic in mind, I can look back on the previous painting analyses to wonder whether there were not moral questions I ought to have asked, perhaps regarding the economic conditions in which easel painting developed, the elitism implicit in the assumption of art’s autonomy, the propagandistic ends of French imperial art. And furthermore, ought I have assumed that ‘we’ see these paintings the same way? Does it do violence to others, with their particular conceptualizations of the world? to you, who I’ve assumed to make up my ‘we’? I am inclined to say that, while the ‘we’ can be used authoritatively or coercively, it may also function as an invitation to share a view of the world that may be refused; that while one may always consider, and perhaps ought at times to consider, the moral implications of paintings, all paintings and all situations in which one looks at painting don’t necessarily demand it. But let us now, if you’ll follow, look closely at one of Guston’s controversial Ku Klux Klan paintings, a painting that, I believe, does demand that we each reflect on the interrelation of the aesthetic, the moral and the epistemological in the problems it occasions.

In The Studio, a white hood with one red and one white hand, respectively holding a paintbrush and a cigarette, paints a self-portrait on a canvas. The (American) viewer recognizes the figure as a hooded klansman, despite the fact that it appears more like a cartoon ghost than a terrorist. One might even be tempted to call the hooded figure, in its pink surroundings, cute. Nonetheless, the concept of ‘klansman’ is enough to make the viewer and the art institution feel a problem and wonder, in the former’s case, how one ought to respond to such a painting, and fear, in the latter’s—as proven by the postponement of the Guston retrospective in 2020 1, the response to the postponement in an open letter signed by over 2,600 artists and curators2, and Hauser and Wirth’s press release for their show of his work in 20213—that it would create problems for the institution that shows these pieces. In the hooded figure in The Studio we recognize the hood first and foremost as a symbol; that is, as standing for concepts the Klan values: racial purity, intolerance, dogmatism and the violence they beget. If we stop here in our reflection on the painting—at the level of mere recognition of what is painted—we might arrive at some vague justification of Guston’s use of the symbol, like the one given in Hauser & Wirth’s press release:

Those defending Guston’s use of the symbol—and that many feel the need to defend his use of it, even when it isn’t under explicit attack, signifies that the painting indeed occasions a problem in the viewer’s experience—claim—anxiously and vaguely—that Guston is—somehow—directly addressing the concepts the hood stands for by means of an allegory. I don’t believe this conclusion is wholly wrong, but it is partial and therefore, I’m inclined to say, irresponsible, insofar as it doesn’t respond to the painting in its particularity but rather distances the institution, the curators, the artist and the artwork from the moral problem it poses by contextualizing the painting—that is, informing the viewer’s perception of it, reflection on it and response to it—with moralizing concepts. Imposing a conceptualization, or interpretation, of the painting doesn’t actually resolve the problem the painting poses but pretends to by shrouding the problem itself from individual viewers in jargon that the institution thinks the viewers want to hear. Providing a conceptualization of the painting fails to encourage viewers to see for themselves exactly how aesthetic reflection relates to moral responsibility in its particular manifestation. The open letter penned in response to the postponement of the retrospective rightly condemns the institutions for shying away from the controversy this painting’s “capacity to prompt its viewers… to troubling reflection and self-examination” might produce.5 But, once again, the letter’s conclusion is partial because, though it proclaims the necessity of individual reflection before the painting without the institution’s mediation, it makes, in one voice that speaks for thousands of signees, contradictory demands. The accusation that the museums are avoiding “uncomfortable questions about museums themselves—about their class and racial foundations” is an easy accusation to level when responsibility isn’t taken for enacting a solution. The public, or a vocal part of it, demands that institutions take responsibility for their dependence on systems of oppression by changing, but simultaneously demands that the institutions continue showing work as usual. Thus, the institution, also a voice that speaks for many, changes its language to retain its public, or customers, but only to the degree that it can continue to show artwork and maintain its institutional authority. A clash of two abstracted voices, two worldviews, two conceptual worlds. But what of the individual who signed the letter? who works at the museum? Is their worldview the same as that expressed in the letter, or does it, like particular perception when subsumed under an abstract concept, lose whatever makes it it? To see how Guston, in this painting, “holds up a mirror… to his own culpability by dint of white privilege and the complicity it engenders” requires that the individual viewer in their particularity—you, me—first perceives the painting in its particularity and, in reflecting on it, conceptualizes it, takes responsibility for it by relating it to their world; relates their conceptualization of the painting to their perception of another’s and, from the other’s point of view, takes responsibility for their own. So, let’s do as the voice in the open letter suggests and each now turn to look at The Studio from our own point of view, beginning not with the the museum or gallery’s conceptualization of the painting but with how we perceive it.

I find it remarkable that this hooded figure, a symbol so charged with significance, also happens to be so visually sparse, little more than a white swathe of paint with Guston’s black dashes for stitches and eyes. I believe it’s this contrast between concept and perception, between loaded symbol and sparse paint application, that accounts for Guston’s preoccupation with the klansman as subject matter, at least in part. How the klansman is painted is so central to The Studio that the act of painting is itself represented: the painted hooded figure paints itself on a painted canvas, using a black line composed of dashes. This representation of the act of painting—of transforming blank white canvas into a symbol by means of a black bounding line—identifies the materials of painting, the white-primed cloth of the canvas and Guston’s dash-based painterly vocabulary, with the klansman’s hood, made of white cloth with stitches and slits for eyes. It is the recognition of this identity between the materials of painting and the materials of the hood that allows me to see this painting’s particular doubleness and thereby to precisely articulate the moral problem it raises. The self-portrait is in progress, the contour of the hood not yet complete, making explicit the relation between material and symbol: symbols, and the concepts they represent, don’t exist apart from a particular material embodiment. A symbol is, in a sense, the materials it is made of. By making the conceptual connection between the materials of painting and the hood, the charged symbol of the klansman is shown to be canvas and paint, thereby stripping it of its conceptual significance. Thus conceptualized, it is merely paint and canvas: the klansman’s hood becomes another composition of painting materials and abstract painterly vocabulary.

According to this conceptualization, this painting—and the act of painting in general—can be a moral act because it strips the hood of its symbolic meaning, which negates the concepts the symbol represents, thereby negating the possibility of their realization. In a world in which the concept of racial supremacy doesn’t exist, violence in the name of racial supremacy couldn’t. A beautiful idea. A utopian resolution of the problem. However, the identity of hood and painting can be seen a second way. Instead of negating the hood’s conceptual significance by reducing it to the materials of painting, this identity can be seen to positively identify painting with the values, intolerance and violence of the KKK. Indeed, as I said just a paragraph before, a symbol is the materials it is made of. To use those materials is to participate in the perpetuation of that symbol and is, therefore, to perpetuate the values it symbolizes: purity, intolerance, inhumanity. From this perspective, the common characterization of the modernist narrative of painting’s progression towards it pure essence, which required the elimination of all foreign elements that could be achieved better in other mediums—including figuration, illusion and narrative—sounds eerily similar to the Klan’s desire for the development of America into a racially pure ethnostate by means of excluding all non-white, non-Protestant people. 6 The painter is not merely complicit, but is as active in the perpetuation of these values as is a member of the Klan.

The Studio, as we would expect from Guston, doesn’t resolve this problem, even if the institutions that show it try to. It is ambivalent, capable of being seen, conceptualized, in two ways, and we are left to decide which side the painting comes out on; or, rather, which side we each, as a painter, or a lover, or a hater of paintings, come out on. On one hand, a return to figuration, which had no place in painting according to what is called the modernist narrative, is a transgression of the modernist exhortation of medium-specific purity that has the power to strip symbols of the concepts they represent and therefore the power to change the world insofar as what is realizable in the world must be conceivable. But, on the other, the materials of painting—whether used figuratively or not—are identified with the klansman’s hood, and, one might conceive, just as the klansman shirks moral responsibility by hiding under the anonymity of the hood, so the painter, and the viewer who chooses to spend their time looking at paintings, might hide behind the anonymity of the canvas. In this sense, The Studio reflects back to me my culpability and complicity, to use the Hauser & Wirth press release’s jargon; but this articulation is misleading, for the painting doesn’t merely reflect but—and this is what the press release glosses over—demands I acknowledge the persistence of the problem. However, a clear interpretation provided by an institution can’t get me to this point. It’s only after I look at the painting in its particularity, after perceiving how the things I recognize are painted, that I can reflect on its ambivalence and decide, for myself, how to respond in light of the discomfort of its irreconcilability. Guston responded to the problem by deciding to paint paintings that remind us of the problem, which both optimistically strive for resolution and pessimistically insist on its impossibility. I am responding by writing this essay. How will you?

But this essay can’t be the end of my response. It leaves me, perhaps us, close to where we started at the beginning of this essay, faced with a problem of recognition, reflection and responsibility; a problem that has epistemological, aesthetic and moral implications. Here I can’t help but reflect on my initial distinction between concepts and perception and the schema I generated from it. The schema is problematic because it attempts to account for a particular experience by subsuming it under abstract concepts that homogenize the particularity of experience. This is also why it is appealing. For, at times, it does seem to me that experience is an interaction between the abstract—schemas, worldviews and institutions—and the particular—paintings, expressions of the worldviews of others, and individuals—both of which are, or ought to be, responsive to, and responsible for, the other. Such a conceptualization of experience might be artificial, but I believe it can—I hope it did—lead to fruitful reflection that then feeds back into the resolution of problems in experience While recourse to a schema won’t do justice to a painting without experiencing—recognizing, reflecting on and responding to—the painting itself, nor will it account for another’s point of view, nor will it provide practical solutions to problems that arise between institutions and individuals; this schema might suggest, with its four ways of relating concepts to perception, our worldview to the worldviews of others, ourselves to the institutions that mediate our experience, that art is not sealed off from the epistemological or the moral but rather can be an occasion to reflect on moral and epistemological problems that arise in our experience of being human. The schema reminds us: first, that we can share a world with others; second, that we can imagine new worlds—utopias—by abandoning current concepts and inventing new ones; third, that we can reconcile worldviews that differ from ours by making our concepts more inclusive; and finally, that reconciliation may, in particular circumstances, be impossible. In the first three scenarios, a problem either never arises or is resolved, but in the fourth it remains. We might say that the acceptance of the problem’s irresolvability, or the successful ignoring of it, is itself a resolution. Sometimes it may be. However, problems, as uncomfortable as they may be, are occasions for changing the world—as I see it, as others see it, and as we share it. The aesthetic is not necessarily true or good, the problems it poses are not always epistemological or moral, but the aesthetic can be an occasion to reflect on the true and the good, insofar as the experience of coming to see an artwork is parallel to the experience of being human: of living in a shared world, striving to make sense of it, trying to improve it and, often, failing to share, to understand, and to improve it much at all.

If you’ll accept this distinction as our starting point, we can generate from it a structure that conceptualizes four ways these two aspects of experience might be related: (1) concepts and perception may be in harmony and thus experience unproblematic; (2) a problem may arise in experience wherein concepts are inadequate to organize perception, so that either old concepts must be wholly abandoned and new concepts created to achieve resolution or (3) concepts broadened in order to subsume incongruous perception; or (4) perception may deny conceptualization while concepts insist on organizing them. According to this schema, it’s only in the first scenario that a problem doesn’t arise. In the second and third scenarios, problems arise in experience that can be resolved. In the fourth, experience is irretrievably divided so that resolution can only be achieved by successfully ignoring the problem.

This schema we’ve generated from our initial distinction presupposes that perception can’t occur without concepts. These concepts may be innate, arrived at inductively, inherited, or created. Regardless of how we come to hold them, we can say that the aggregate of our concepts compose our world, or conceptualization of it. Together concepts paint a picture of the world as one sees it, a worldview, in light of which one recognizes and reacts, consciously or unconsciously, at any given moment. This worldview is the structure through which experience is understandable; is where we stand, a way of seeing, a vocabulary and grammar that describes this world, a limit to what is conceivable, what is realizable; is the world that we perceive. Perceptions are presentations of that conceptual world in its particularity, particular instances of abstract concepts, which can be, and often are, harmonious with one’s conceptual structure. But perceptions can also be inarticulable in a given vocabulary and can push, perhaps even puncture, the limits of what is conceivable, can change our way of seeing, which is to change our world. It is tempting, perhaps inevitably so, to believe one’s own worldview to be an accurate picture of the world as it really is, as if the world were an object we could come to understand through empirical observation, as through the lens of a camera, microscope or unbiased eye. But the world is conceptualized differently by different people, their actions and products not mere objects that can be known empirically but expressions of their subjective worldview. The world we perceive is composed of the worldviews of others, at least in part. How we resolve a problem between our conception of the world and our perception of others’ worldviews—that is, between our concepts and our perception of the concepts of others—is a question, not of coming to know the objective world merely, but of coming to see another’s conception of that world and consequently relating theirs to our own. It is a problem of recognizing, reflecting on and responding to another’s worldview. If we emphasize the recognition, we might call such problems that arise in experience epistemological; if we emphasize the responsibility, moral. I am going to emphasize reflection and call them aesthetic problems.

Art occasions relations between the viewer’s conceptualization of the world and their perception of the artist’s conceptualization of the world as embodied in the artwork—relations parallel to those between perception and concepts sketched above: (1) the viewer may find that they share a world with the artwork; (2) they may find such difference between their worlds that the viewer can only enter the artwork’s by abandoning their own; (3) the viewer may expand their conceptual world in order to assimilate the artwork’s to it; or (4) the viewer may insist on using the concepts of their world to understand the artist’s while finding reconciliation to ultimately be impossible, which may result in preoccupation with the problem it presents to them or in walking away from it, perhaps to look at a more pleasing painting. This parallel we’ve set up between the relation of concepts and perception in our experience of the world and our experience of art suggests that reflecting on how we resolve the problems that arise in artistic experience, which artificially affords us reflection independent of recognition and responsibility as is demanded in our experience of the world, might prepare us to better recognize and respond when our world, or the interrelation of our world with others’, becomes problematic. To do so, let’s imagine four types of artwork that correspond to our schema. I will restrict the instances of each to painting, for painting, which addresses itself to the eye, is especially suited to problematize how we see the world. Paintings show us that others see the world differently than we do, so that we might see, or try to see the world differently, a different world.

Paint’s potential to mimic the appearance of different materials, textures, volumes and atmospheres can produce paintings that reinforce a worldview in which vision is a neutral means of coming to know an objective world, wherein perception is unproblematic because it seems to transmit to us a conception of the world as it really is. Such paintings don’t problematize the relation between the viewer’s conceptual world and their perception of the painting, but rather claim to represent the world accurately, as if through a pane of glass. I will call this first type of painting ‘descriptive painting’ because such a painting claims to describe the world as it is. A descriptive painting assumes congruence between the view of the world it presents—how it is perceived by the viewer—and the viewer’s conceptualization of the world, thus situating itself as an extension of the viewer’s world. The viewer’s concepts, and therefore their way of seeing and the vocabulary they use to describe what they see, are adequate to it already, so the relation between their concepts and their perception of the painting is unproblematic. Let’s look at Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps as a particular instance of our concept of descriptive painting. With imperceptible brushstrokes, naturalistic modeling and atmospheric perspective, the material properties of paint—its viscosity, color, handling—are made invisible, transformed into the material properties of other objects. Indeed, the painting announces itself as a window into a world not of paint but of familiar objects made from identifiable materials: flesh, leather, iron, stone. It presents a world that appears to behave according to the same laws that a viewer, who believes their eyes accurately tell of a world characterized by extension and material differentiation, expects the world to behave according to, and manipulates this expectation for a rhetorical end. Napoleon, with flesh so convincing it seems it might yield to touch, is painted wearing ornate clothing, pointing forward and upward astride a rearing horse, in the process of traversing the mountains with an army in the background. The horse’s glistening eyes seem to roll and its tensed muscles to twitch under its coat as its power is restrained by Napoleon’s utter control. Paint is manipulated to imitate the appearance of things as one who believes vision to record the effects of natural laws would expect. The painting is continuous with their conceptual world and by means of this continuity of concepts constructs a visual enthymeme that can be articulated as follows: Great paintings mimic the visual effects caused by natural laws; Napoleon appears, as if he himself were before our eyes, valiantly leading his troops over the rocky Alps whereon his name is carved alongside, and larger than, the names of great leaders throughout history; therefore, tracing the causal chain backwards, Napoleon is by natural law a great leader (and David a great painter). By stylistically establishing a world continuous with the viewer’s own, to which their way of seeing, and thus their vocabulary, is already adequate, and organizing that shared vocabulary into an argument, the painting claims to describe the world as ordered by natural laws and the qualities of the things in it. In this painting, description is used to the rhetorical end of persuading the viewer that, just as surely as they can see the clouds in the sky or the mountains on the horizon, they see their emperor is a great man.

But paint, in addition to being able to mimic the material properties of objects seen in the world, has material properties of its own, which can be used to make explicit the potential gap between concepts and perception. A second type of painting does the opposite of descriptive painting by restricting itself to the material properties of its medium, thereby creating a world of paint all its own. I will refer to this conceptualization of painting as ‘autonomous painting’ because such a painting creates its own vocabulary and uses it to define itself. In relation to an autonomous painting, the viewer must be born again into this new world by abandoning their normal way of seeing in order to form new concepts in light of the painting’s internal logic, the laws natural to paint. The relation between the viewer’s concepts and perception is problematic because an autonomous painting demands that it is like nature itself, absolute creator of new forms, and the viewer that clings to concepts external to the work, thereby failing to adapt to this nature, is a lifeform not long for the painting’s world. Mark Rothko’s No. 13 (White, Red on Yellow) is a particular instance of autonomous painting. No. 13, indifferent to the normal concepts of the viewer, announces itself to be a world of its own: it is large and so fills the viewer’s field of vision that it seems to engulf them like an environment; it is always changing because staring at saturated pigment creates after-images of complimentary colors that move as the viewer’s eyes move, thereby modulating the appearance of the pigment applied to the canvas; furthermore, like nature, it seems less to be something made by a human than something that simply is because its history is unknowable insofar as the process by which it is made obscures that very process. Once the viewer relinquishes their usual concepts—that is, leaves their world behind—and allows theirself to enter this new world that is the painting, they must let their perceptions teach them the concepts this world demands. Starting with all they have—what they can perceive—they begin to build new concepts: they see the shape of the canvas, the occasional glob of paint or brush bristle left behind, the relative effects of color—and, in looking, they realize that these perceptions occasioned by the painting are themselves mimicked in the painting: the shape of the large canvas is represented by smaller rectangles within; the physiological effect of the viewer’s eye layering after-images of color over the painting is reproduced by the material layering of paint on the canvas; the physical qualities of the materials, such as shadows cast by globs of paint, are reproduced in paint, as by a dark dot on its surface. By representing in paint the perceptions its own paint occasions in the viewer, the painting shows the viewer the concepts appropriate to its world: concepts of, what we might call, ‘rectangle,’ ‘layering,’ ‘paint glob;’ that is, concepts that grow out of the material nature of its medium. But we need not call them by these words; we could just as easily gesture or make up new words for our perceptions and the new concepts we abstract from them because the painting presents what it represents and represents what it presents. To enter this world of paint, the viewer must become a child again and through their sense of sight begin to learn a new conceptual structure, a new language, a new world.

Taking advantage of paint’s material potentials for both mimesis and abstraction, a third type of painting depends on the viewer’s concepts to make intelligible what are initially unintelligible aspects of its appearance by problematizing the relation between concepts and perception in such a way that the viewer’s perception of the painting is close enough to, but different enough from, their conception of the world that the relation between concept and perception is problematic, but ultimately reconcilable. I will call these paintings ‘correlative paintings’ because bringing concept and perception into harmony requires the mutual adjustment—the co-relation—of both: the expansion of concepts to include novel perceptions and the conformation of novel perceptions to fit within those concepts. For instance, Edouard Vuillard’s At Table. Painted with a narrow spectrum of values and hues, the grayish brownish daubs of paint, made by a hand in motion that discovers the form its subject matter will take as it moves, assert that they are indeed paint applied to a surface while also representing, miraculously, a scene of people at a table. That the viewer perceives those patches of paint both to be paint and to be a table with three figures shows how concepts can expand to include perceptions and, conversely, how perceptions can be informed by those concepts in order to assimilate those daubs of paint to conceptual categories common to a domestic scene. Take, for example, the hand belonging to the figure at the right of the canvas, which, at first, may not be intelligible as a hand at all: in color, paint application and form the hand is nearly identical to the tablecloth that surrounds it, lacking any outline to delineate it from its background,—and yet, it is a hand.

Some combination of direction of brushstrokes and vicinity to a black silhouette suggests the viewer’s concept of ‘hand,’ while in relation to the suggestion of the concept of ‘hand,’ the paint daubs appear more hand-like than they may have at first. By correlating Vuillard’s paint daubs with the viewer’s concept of ‘hand,’ and vice versa, an equilibrium is reached between concept and perception: the problem of what type of thing the paint daubs represent is resolved. The painting’s patchwork of brushstrokes together with the viewer’s conceptual categories knit a harmonious scene populated by human bodies, lace tablecloths, flowers and glass bottles. But—and here is where correlative paintings, as exemplified by Vuillard’s At Table, differ from descriptive paintings like David’s Napoleon—in a correlative painting, the viewer must, at the same time that they see lace and flowers, also see the lace and flowers to be paint. The perception of paint and the recognition of a concept are inextricably interrelated. At Table doesn’t claim to describe a hand in the way David’s painting claims to describe the flesh and bone that compose Napoleon’s right hand. Rather, Vuillard’s painting uses paint’s materiality to occasion the recognition of painted things that appear very different from instances of those things as they are normally perceived in the world, showing forth the potential rift between our abstract concepts of a type of thing and our particular perception of an instance of a thing while occasioning the resolution of this rift by broadening our concepts to subsume the particular, albeit painted, instance.

Finally, there is a fourth type of painting, which also occasions in the viewer a feeling that there is a problem between concept and perception, but insists that the relation between the two is not so reconcilable as correlative paintings suggest. Instead, for this last type of painting, the relation of concept to perception is one of continual severing and suturing, slicing and stitching: a problem without harmonious resolution. I will call this type of painting ‘ambivalent painting,’ in the sense of showing simultaneous and contradictory attitudes toward something, because it occasions a divided experience in which concept and perception are unavoidable but irreconcilable. The following two paintings by Philip Guston are such paintings. The experience they occasion is necessarily fragmented: concepts are always inadequate to wholly account for perceptions, but perceptions nonetheless appeal to concepts to be understood. No amount of suturing can return experience—that is, the world—to harmony: nevertheless, these paintings attempt to nail it back together. This type of painting, or rather, these paintings, throw the schema from which their type was derived into question because they problematize the very function of a schematic, or conceptual, understanding: can an abstract schema account for particular experience? Can a concept be adequate to particular perception? Despite the risk of denying its own schema’s validity, it is here, with these paintings and the problems they pose, that we will spend the rest of this essay because it is from here, in the problems that arise between our perception and concepts and between our concepts and perception of others’ concepts, that the schema came.

Let’s begin by describing Guston’s painterly vocabulary used in these paintings as it is perceived in Ancient Wall. First, a description of the types of things we recognize in the painting. In its top half the viewer perceives a black sky above a red brick wall, over which a mass of bare legs dangle, pink and knobby with dash-like hairs. The lower half of the painting is filled with a mass of diverse objects that can only hesitatingly call shoe soles, some connected to red stalks—bloody limbs?—that sprout from an area of black paint—perhaps a shadow?—at the bottom of the canvas. But this description, being verbal, emphasizes those things that are recognized, more or less, to belong to concepts continuous with our conceptualization of the world, concepts for which they have words: ‘sky,’ ‘brick,’ ‘wall,’ ‘leg,’ ‘shoe;’ whereas many other things in the painting, though they are perceived to be similar in form and paint application to these recognizable things, refuse to fit neatly into those same concepts,—or any concept, for that matter—so that we might hesitate to call the area of black paint a shadow, opting instead for ‘that shadow-like thing.’ Such a description that emphasizes words, or abstract concepts of things, can only be partial for a painting that is so emphatically paint. We must now turn to describe the same painting with emphasis, not on what types of things are recognizable, but the perception occasioned by the paint itself.

The painting is composed of marks from a painterly vocabulary of which the dash-like brushstroke made by a quarter inch flat brush is the smallest unit, as in the leg hairs; and from a limited vocabulary of colors—primarily red, black and white—employed separately and so mixed to make pinks and grays. The dashes, when placed end to end, form a ragged line or, when made with a large brush, compose the swathes of paint that cover the canvas. The ragged line sometimes functions as a contour that transforms a swathe of paint into a recognizable thing; sometimes that same ragged line is simply that, a painted line that can’t be seen to function as the contour of any particular thing, despite appearing formally indistinguishable from the aforementioned lines that bound something recognizable. In these latter cases, the line is an instance of a painterly vocabulary applied without representational function: paint perceived as paint in contrast to a painted instance of a recognizable concept. This double use of paint problematizes our attempt to assimilate our perception of paint to our concepts by employing a vocabulary of painted forms in two exclusive ways: on the one hand, the units of the vocabulary are composed so as to occasion the recognition of particular instances of types of things; on the other, the units are simply perceived to be paint applied to a canvas in an idiosyncratic manner.

This doubleness exemplified by Guston’s painterly vocabulary, in which the same brushstroke can be recognized to function in two different and contradictory ways—either representing a concept or simply presenting paint for perception—applies to Ancient Wall as a whole. The painting, like an image that occasions a gestalt shift, presents two views: two different paintings on a single canvas that represent two contradictory views of the same scene: the first, the view the painting presents to perception the second, a view that requires conceptual reorganization to see. The painting at first—the ‘first painting’—is perceived to be a landscape scene with a pile of shoes in the foreground, which takes up the bottom half of the canvas, in front of a brick wall with legs hanging over it in the background, which, with a black sky, takes up the top half of the canvas. An unsettling scene of limbs without bodies made more unsettling when we reflect on how we recognize these things to be limbs and shoes although they are unlike any limbs or shoes we, or at least I, have ever seen. We experience a problem of how to organize our perception of the painting so as to assimilate it to our worldview, subsume it under concepts already held. We can only continue to look, to perceive the painting more particularly, letting the faculties of conceptualization and perception wrestle. Eventually—in my case, hours later—a second way to see this painting, a ‘second painting,’ is perceived; or rather, conceptualized. To see this ‘second painting,’ the viewer must recognize in the ‘first painting’ instances of the concepts ‘leg,’ ‘foot,’ ‘shoe’ and ‘sole’ and subsume them under another more comprehensive concept: that of the body as a whole, in relation to which the concepts are parts that are, in the first painting, severed from one another. By conceiving of their potential continuity,—that in relation to a ‘body,’ a ‘leg’ is continuous with a ‘foot’ that is sometimes in a ‘shoe’ with a ‘sole’—we can conceptually reconnect the shoe soles in the foreground to the legs dangling over the wall behind by imaginatively flipping the bottom half of the canvas. Reorganized conceptually, the bottom half of the canvas becomes a view of the legs hanging over the wall seen from another perspective, from underneath, as if we each—I—could enter the scene in the first painting, lay on the ground with my head touching the brick wall to look up at the shoe soles of the shod feet connected to the dangling legs while simultaneously seeing the scene that I’ve entered in the top half of canvas. Now what appeared in the first painting to be a pile of shoes turns into a canopy of feet in the second, the black shadow-like-thing from which the feet were sprouting in the first transforms into the sky above the wall at the top of the canvas, the bloody limbs continuous with shoe soles flip to be the dangling legs reflecting the red light of the brick wall behind them. The single eye painted in the bottom right corner of the canvas confirms this view: a representation of the concept of vision separated from a body, suggesting another view from within the painting. A view that is impossible for me, who can’t physically enter the painting, to perceive, but is possible for me to conceptualize.

But this doesn’t resolve the problem. This second conceptual view can only be maintained by an act of mental gymnastics because it requires a reconceptualization of the painting that contradicts the perception of it. Our experience of the painting remains irresolvable because the single canvas contains within it two contradictory paintings: the first, perceived to be a unified view of a landscape with fragmented body parts in which the bottom and top halves are respectively foreground and background; the second, a fragmented view of a landscape with unified body parts, in which the top and the bottom halves must be conceptually reorganized so that the viewer simultaneously perceives a view of the scene looking at the canvas, as one looks at a scene from a window, and a view from within that scene, but perpendicular to it and from beneath. The painting as a whole occasions a problem in the viewer’s experience in which all the perceptual data can’t be subsumed under concepts, but neither can concepts be fully abandoned because some perceptions are indeed recognized as belonging to them: on the one hand, the viewer’s perception in which the landscape is unified required the fragmentation of their concept of body; on the other, the conceptualization that unifies the limbs into a whole body fragments the viewer’s perception from the conceptualized view. The painting(s) tempt(s) us to resolve this problem while symbolizing its impossibility in the two what I can only call ‘leg-like-things’ hanging over the wall on the right, deflated by nails: a means of uniting and puncturing, or uniting by puncturing. In the experience of this painting, the problem between concept and perception can only be resolved at the cost of one or the other. That is to say, it can’t be.

In looking at the problems that arise between concepts and perception in the double function of Guston’s painterly vocabulary in general and the double view in Ancient Wall, I’ve limited my analysis to problems that arise between the perception of paint and the recognition of the paint as a thing belonging to a concept that is in itself unproblematic. I’ve used the term ‘problematic’ to describe experience in which a problem arises and occasions reflection, in contrast to the contemporary moralizing usage of the term. However, this term is commonly used to describe statements or actions that pose moral problems, usually to condemn those statements or actions. Thus far, my reflections have emphasized the aesthetic, so I’ve used the first sense of the term because, as I said in the beginning, art seems to grant reflection a degree of autonomy from epistemological claims of truth and moral demands of responsibility, to create a space in which to work out problems without practical consequences. But some paintings make clear that this autonomy is indeed artificial; that aesthetic reflection rubs up against moral responsibility, just as it rubs up against the epistemological problem of recognizing abstract concepts in particular perception. With this moral sense of problematic in mind, I can look back on the previous painting analyses to wonder whether there were not moral questions I ought to have asked, perhaps regarding the economic conditions in which easel painting developed, the elitism implicit in the assumption of art’s autonomy, the propagandistic ends of French imperial art. And furthermore, ought I have assumed that ‘we’ see these paintings the same way? Does it do violence to others, with their particular conceptualizations of the world? to you, who I’ve assumed to make up my ‘we’? I am inclined to say that, while the ‘we’ can be used authoritatively or coercively, it may also function as an invitation to share a view of the world that may be refused; that while one may always consider, and perhaps ought at times to consider, the moral implications of paintings, all paintings and all situations in which one looks at painting don’t necessarily demand it. But let us now, if you’ll follow, look closely at one of Guston’s controversial Ku Klux Klan paintings, a painting that, I believe, does demand that we each reflect on the interrelation of the aesthetic, the moral and the epistemological in the problems it occasions.

In The Studio, a white hood with one red and one white hand, respectively holding a paintbrush and a cigarette, paints a self-portrait on a canvas. The (American) viewer recognizes the figure as a hooded klansman, despite the fact that it appears more like a cartoon ghost than a terrorist. One might even be tempted to call the hooded figure, in its pink surroundings, cute. Nonetheless, the concept of ‘klansman’ is enough to make the viewer and the art institution feel a problem and wonder, in the former’s case, how one ought to respond to such a painting, and fear, in the latter’s—as proven by the postponement of the Guston retrospective in 2020 1, the response to the postponement in an open letter signed by over 2,600 artists and curators2, and Hauser and Wirth’s press release for their show of his work in 20213—that it would create problems for the institution that shows these pieces. In the hooded figure in The Studio we recognize the hood first and foremost as a symbol; that is, as standing for concepts the Klan values: racial purity, intolerance, dogmatism and the violence they beget. If we stop here in our reflection on the painting—at the level of mere recognition of what is painted—we might arrive at some vague justification of Guston’s use of the symbol, like the one given in Hauser & Wirth’s press release:

In this group of paintings, Guston holds up a mirror not only to America’s racist past and present, but to his own culpability by dint of white privilege and the complicity it engenders. In ‘The Studio’ (1969), one of the artist’s most iconic paintings, Guston depicts himself in the grand tradition of Western art, as an artist at work before his easel. In this allegory of painting, however, Guston occupies not the exalted role shown in celebrated self-portraits by such forebearers as Gentileschi, Vermeer, Velazquez, and Courbet, but as one of his own hooded figures, cigar in one hand and paint brush in the other, hood splattered with blood red marks. By identifying himself with the enemy, Guston creates a radical image of an artist wrestling with both the act of painting and his own role in the state of the world. 4

Those defending Guston’s use of the symbol—and that many feel the need to defend his use of it, even when it isn’t under explicit attack, signifies that the painting indeed occasions a problem in the viewer’s experience—claim—anxiously and vaguely—that Guston is—somehow—directly addressing the concepts the hood stands for by means of an allegory. I don’t believe this conclusion is wholly wrong, but it is partial and therefore, I’m inclined to say, irresponsible, insofar as it doesn’t respond to the painting in its particularity but rather distances the institution, the curators, the artist and the artwork from the moral problem it poses by contextualizing the painting—that is, informing the viewer’s perception of it, reflection on it and response to it—with moralizing concepts. Imposing a conceptualization, or interpretation, of the painting doesn’t actually resolve the problem the painting poses but pretends to by shrouding the problem itself from individual viewers in jargon that the institution thinks the viewers want to hear. Providing a conceptualization of the painting fails to encourage viewers to see for themselves exactly how aesthetic reflection relates to moral responsibility in its particular manifestation. The open letter penned in response to the postponement of the retrospective rightly condemns the institutions for shying away from the controversy this painting’s “capacity to prompt its viewers… to troubling reflection and self-examination” might produce.5 But, once again, the letter’s conclusion is partial because, though it proclaims the necessity of individual reflection before the painting without the institution’s mediation, it makes, in one voice that speaks for thousands of signees, contradictory demands. The accusation that the museums are avoiding “uncomfortable questions about museums themselves—about their class and racial foundations” is an easy accusation to level when responsibility isn’t taken for enacting a solution. The public, or a vocal part of it, demands that institutions take responsibility for their dependence on systems of oppression by changing, but simultaneously demands that the institutions continue showing work as usual. Thus, the institution, also a voice that speaks for many, changes its language to retain its public, or customers, but only to the degree that it can continue to show artwork and maintain its institutional authority. A clash of two abstracted voices, two worldviews, two conceptual worlds. But what of the individual who signed the letter? who works at the museum? Is their worldview the same as that expressed in the letter, or does it, like particular perception when subsumed under an abstract concept, lose whatever makes it it? To see how Guston, in this painting, “holds up a mirror… to his own culpability by dint of white privilege and the complicity it engenders” requires that the individual viewer in their particularity—you, me—first perceives the painting in its particularity and, in reflecting on it, conceptualizes it, takes responsibility for it by relating it to their world; relates their conceptualization of the painting to their perception of another’s and, from the other’s point of view, takes responsibility for their own. So, let’s do as the voice in the open letter suggests and each now turn to look at The Studio from our own point of view, beginning not with the the museum or gallery’s conceptualization of the painting but with how we perceive it.

I find it remarkable that this hooded figure, a symbol so charged with significance, also happens to be so visually sparse, little more than a white swathe of paint with Guston’s black dashes for stitches and eyes. I believe it’s this contrast between concept and perception, between loaded symbol and sparse paint application, that accounts for Guston’s preoccupation with the klansman as subject matter, at least in part. How the klansman is painted is so central to The Studio that the act of painting is itself represented: the painted hooded figure paints itself on a painted canvas, using a black line composed of dashes. This representation of the act of painting—of transforming blank white canvas into a symbol by means of a black bounding line—identifies the materials of painting, the white-primed cloth of the canvas and Guston’s dash-based painterly vocabulary, with the klansman’s hood, made of white cloth with stitches and slits for eyes. It is the recognition of this identity between the materials of painting and the materials of the hood that allows me to see this painting’s particular doubleness and thereby to precisely articulate the moral problem it raises. The self-portrait is in progress, the contour of the hood not yet complete, making explicit the relation between material and symbol: symbols, and the concepts they represent, don’t exist apart from a particular material embodiment. A symbol is, in a sense, the materials it is made of. By making the conceptual connection between the materials of painting and the hood, the charged symbol of the klansman is shown to be canvas and paint, thereby stripping it of its conceptual significance. Thus conceptualized, it is merely paint and canvas: the klansman’s hood becomes another composition of painting materials and abstract painterly vocabulary.

According to this conceptualization, this painting—and the act of painting in general—can be a moral act because it strips the hood of its symbolic meaning, which negates the concepts the symbol represents, thereby negating the possibility of their realization. In a world in which the concept of racial supremacy doesn’t exist, violence in the name of racial supremacy couldn’t. A beautiful idea. A utopian resolution of the problem. However, the identity of hood and painting can be seen a second way. Instead of negating the hood’s conceptual significance by reducing it to the materials of painting, this identity can be seen to positively identify painting with the values, intolerance and violence of the KKK. Indeed, as I said just a paragraph before, a symbol is the materials it is made of. To use those materials is to participate in the perpetuation of that symbol and is, therefore, to perpetuate the values it symbolizes: purity, intolerance, inhumanity. From this perspective, the common characterization of the modernist narrative of painting’s progression towards it pure essence, which required the elimination of all foreign elements that could be achieved better in other mediums—including figuration, illusion and narrative—sounds eerily similar to the Klan’s desire for the development of America into a racially pure ethnostate by means of excluding all non-white, non-Protestant people. 6 The painter is not merely complicit, but is as active in the perpetuation of these values as is a member of the Klan.