Eric Bayless-Hall

– EMBODIMENTS: A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION

Tomato Mouse Gallery, October 22-November 19 ︎︎︎

Gregor's paintings warrant long looking. And look back. The longer we stay before them – looking, considering what we see – the more they show themselves to see. We discover, not only new figures, textures, patterns not noticed, but entire views overlooked and constellations of ideas that confirm the working of a critical intelligence embodied in these works when we remain with them and learn the world they inhabit, look at, express and question. If they seem strange at first blush, they will not cease to be strange after an hour – if anything, they will appear more peculiar – but a logic will begin to reveal itself that makes their strangeness intelligible, and profound.

*****

There are common themes and subjects of Gregor's paintings that one finds time and again in them. Where there is paint, it is spilt. Where there is tape, it is peeled. Where there is paper, it is torn or folded. Where there are nails, some are pulled. Where there are doors, they are ajar. Where there are windows, they look out onto nothing in particular, if they're not bricked or boarded up. Where there are rooms, there's no clear way out – or, often, about them: no simple way to make sense of these spaces and how we might move through them.

Multiple paintings make use of reverse perspective, where, instead of receding away from the viewer toward a vanishing point as they do in linear perspective – roughly the way cameras see – objects and surfaces closer to the viewer instead converge toward her. The technique, often associated with Byzantine art, has a history in Christian icon painting that is not irrelevant to Gregor's work. We find acknowledgments of their work's connection to an icon painting tradition in History Painting – where a yellow piece hangs above the door in one of the icon's traditional locations – in Medium – whose haloed figure points out past its gilt manuscript – in Wittgenstein's House – where a veritable crucifixion scene defies the perspective of the wall it's hung on to be orthogonal to the surface of the painting – and perhaps, with a stretch, in the upside-down cross in Insulation.

But reverse perspective in Gregor's hands does more than harken to a history. It traps us in the spaces the painter has made. The lower half of Insulation, for example, may seem at first to put the viewer on the floor at the far end of a room that recedes toward a boarded up window, looking up toward the rafters. But another view, which is perhaps more awkward to enter for viewers used to linear perspective, but a view that holds as we continue to look at this painting, is to be had by seeing the boarded up window as the closest surface to us, the exterior wall of a room we are looking down into through the rafters. There is an important other view in the top half of this painting that we will have to consider when we return to see it in detail, but the thing to notice now is that the perspective of this bottom half closes in on us as we look. If we follow the walls on either side toward the spot where they'd converge, we are fixed to a point. Move all we might, the point from which we can view the painting – so perspective lines suggest – is rigidly determined.

I will pursue this theme of being fixed – perhaps trapped – for a moment, for it shows up in more ways than reverse perspective. In Wittgenstein's House, in the left-hand room of that diptych, there is a mirror leaning against the far wall facing us, and all it shows is a series of doorways – or: another mirror and four iterations of reflections – and a lamp. We are not in the room. Our view of it is impossible. Or: we are invisible – or: a lamp – in which case, being in the room, we can't get out: the wall is solid behind us. We either can't get in or can't get out.

This latter interpretation, that we are in and can't get out, agrees prima facie with the title and subject of Escape Attempt, where every possible way out is blocked, by boards or bricks, and the image of the outside world is in fact just a painting of a landscape – as we know once we see the small signature in its corner – no escape, really, except into a painting. But seeing as we're already looking at a painting, this gets us nowhere new. So much of this painting is curious, not least that it's unclear whether we've been boxed in or whether we've boxed ourselves in, whether we've come upon a scene rife with clues of another's activities or whether we've done this, laid this brick, nailed these boards, painted this door – perhaps hoping somehow to make an exit – built this structure to contradict the perspective of the room. Who's trying to get out, and are they sure they're not actually trying to stay in?

*****

This leads me to thoughts too general to be considered in Gregor's paintings, but, taking the domain of the critic to be not only the relevance of our experience to the works before us, but also the relevance of these works to our experience, I trust I'll be humored in taking liberty to digress briefly and consider some themes of experience Gregor's paintings embody.

Once we begin looking at a work, we can see it better by looking longer, making connections among what we see, building tentative patterns bolstered or challenged by what we see next, conceptualizing and reconceptualizing what we observe to sniff out inconsistencies in our understanding. This process, when attended by a sense of a guiding intention – that these connections, patterns and concepts are supposed to be there – expands our understanding of the thing before us and our appreciation of it. This process of beginning really to look at a work is intelligible enough, even if underdescribed, but it rests on a mystery: it requires that we already see something of the work to begin relating parts to. Coming to see the work is an activity we begin only once we already see it – or: we can begin looking at it once we have already begun seeing it. Once we are in the world of the painting, so to speak, we can find out where we are. But how do we get into the world of the painting in the first place? We must already be in it; or else we will never enter it – not without a miracle, anyway. This is one of the mysteries of understanding: once we've started, we can go further, but we don't know – can't, it seems – how we got started at all.

As with paintings, so with existence. How we got started living: in these bodies, in this world – we don't know. Part of our condition seems to be an ignorance of our origins and of the grounds of our existence. If we weren't in the world already, we wouldn't know how to get in. And since we're in it, we don't know what it would mean to get out, or how. Will death do it, for instance? Will faith? Will science? Philosophy? Love? I can't consider our options here, but take it as unknown whether they can – even conceivably – lead one out of the world. We are here embodied in it. Vision affirms the fact. The vanishing point of the horizon over the water, while suggesting infinite distance, draws the line where sea and sky meet as the floor to the walls of a dome to close us in. It's our condition, but that doesn't mean we're at home here. That the world doesn't feel at times a prison. Or that we don't at times feel trapped in our bodies and alienated from the world, apart from one another, "ringed round" – as Pater says – "by that thick wall of personality through which no real voice has pierced… each mind keeping as a solitary prisoner its own dream of a world." Only that every attempt to escape concludes in a return to the world and to our bodies in it – or: if death really is an out, that word hasn't gotten back to the living.

*****

Gregor's paintings send me off on this train of thought because they picture in different ways this fact of existence, that we are already in it, already begun, potentially trapped, though we don't know how or to what end, which is a fact with roots deeper and branches other than painting, but which is constitutive of painting as an object of understanding and a medium of communication.

In addition to the themes of being within and being without, seen most clearly in the spaces and viewpoints of Wittgenstein's House and Insulation, looking out and being looked at are themes of Gregor's paintings seen in the peephole in History Painting, the nail holes that stare back at us in Escape Attempt, and the faceless figure of Medium. These paintings threaten to trap and alienate us – from them, their painter, and from ourselves – if we should enter them.

There is a theme in multiple paintings of a potential view from outside the painting. The figure in Medium points beyond itself; the door and windows of Escape Attempt, as well as the painting in that painting, suggest views and ways out; the wall in Strange Loop is broken through to its supports. But the figure in Medium points to the painting; the ways out in Escape Attempt are all thwarted; and behind the wall in Strange Loop is more wood. Past these materials is perpetually more material.

So much seems inevitable for material's attempts to get beyond itself. But a possible route is open, at least seems open – at least seems like it might be open – to escape through ideas, which don't seem to subsist materially. In the three paintings I've just mentioned, Medium, Escape Attempt, and Strange Loop, we find geometrical sketches, partially filled in, that suggest forms that need work to complete – work, that is, on the part of the viewer. We might imagine these paintings taking the Platonic view of geometrical forms: we've never seen a prism, only inadequate semblances: the real form – the really real – is beyond perception, apprehended in thought. Similarly the torn floor-plan in Escape Attempt describes the room we're looking at but from above, a view of the space that can only be had imaginatively, by the mental work of the viewer. These are ways a painter might try to transcend their art's material, by suggesting ideas that are occasioned by the paint, the marks, the surfaces, the subjects, but not identical with them. This thought – that we might by perceptible means suggest transcendent realities – edges into contested territory of millenia. One painter might deny this possibility of transcending materials; but another might identify a painting, not with its materials, but with its ideas, such that even should the canvas burn, the painting – a form – survives.

*****

I don't have a horse in that metaphysical race, but Gregor's paintings seem to be questioning their nature – means, ends and essence. And the struggle of the inquiry, taken by a painter on behalf of painting, seems internal to the works in Embodiments. It is tempting to speculate further about what this painter thinks painting is, based on the pregnant titles and subject matter of the work – to ask what the concepts of assimilation, escape, insulation, loops, medium, foundation – Wittgenstein, for Christ's sake – Christ, nailing, taping, tearing, joining, scaffolding, perspective, looking, being looked at, being within and being without tell us about Gregor's conception of painting. But to ask that now would be sheer speculation. To get an answer to that question – or, more realistically, a path toward an answer that we might all follow out for ourselves – we have to find the right position from which to ask it. These titles, these subjects, can't be just irrelevant to the works – I trust them too much to think that. But their relevance must consist in more than our existential speculations, for these have nothing to do with the concrete objects before us. The duty of the critic – which is the duty of anyone on the listening side of a conversation – is to find what it is that makes these words and references relevant. We say a great deal about painting and about words pursuing these questions from where we stand, but we say nothing about Gregor's paintings until we look at them in ways that words can't quite reproduce.

They share many themes, but they are also each unique, and while we can – and should – ask whether Faulty Foundations 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are to be taken as a series, since their names and consistency of size suggests a single effort embodied on many panels, there is a patent diversity of purposes and achievements among the rest. To see these better, let us look at two specimens uniquely and reflect on what painting for Gregor involves.

*****

There is a pattern I observe in Medium: spaces and forms extend beyond the bounds set for them. The faceless figure is centered in an arched space that it points beyond. A dark brown stretcher bar roughly mirrors that finger in extending from a stack of vertical bars, opposite the figure, across the width of the painting. The horizon line of the inset picture, framed in the bottom right, continues out of that frame, wraps up and around the left edge of the painting and descends to become the outline of the figure's finger. The yellow pattern behind the figure seems to spill through the bottom of its frame and spread, diluted, out and to the right. To say that they extend beyond the bounds set for them is to say that for these forms bounds are set – that there are distinct spaces and places where forms principally are – and that those bounds are then exceeded. Why then bound them in the first place?

Another pattern. The material that constitutes individual forms and the way it is applied can vary wildly within that form. The aforementioned stretcher bar, for example, that runs across the painting appears, at the right, dimensional – rendered by striations of O so thinly painted strokes! – as it's overlaid by the white trace of a paint roller, and, to the left of the pointing figure, it is flat, sheer paint, dripping onto its own shadow. The horizon line that escapes the inset picture is at various points on its circumnavigation made of paint, graphite, and, for a stretch, the negative space between two surfaces. What read as continuous forms are shown to be composed by diverse means and in diverse manners. If unified, why complicate them? If various, why unify them?

A step toward answering these questions – though only a step – is taken when we read these patterns as an analysis of – or: inquiry into – the material rendering of forms. The graphite of an architectural sketch in the inset picture becomes a grey painted line still thin enough to resemble a thick line of graphite – the line seems to mimic itself. And the pile of stretcher bars that face the pointing figure seem to mimic it – pointing past it and holding the inset picture as it holds its gold manuscript. And a circle of paint seems to have been squeezed out of the tube clockwise above the inset picture, let to dry, and then painted over with a spectrum ranging from what I take to be the original brown pigment of the impasto to yellow, and that impasto is furthermore given highlights on its topside and a painted shadow beneath it. This painting seems to be looking at, thinking about and depicting itself.

An inquiry of sorts is underway, visible in the manipulation of materials and the arrangement of forms on the canvas. Indeed the two patterns so far observed are in fact describable as one: the extension of forms beyond their set bounds, where this entails the interaction of forms with one another, just is the material variation of a form's composition, namely, the form of the painting as a whole. Each is an aspect of an inquiry into what (this) painting is.

Seen as internal relations – relations made within the painting to other parts of the painting – all that's been observed lights up its circular composition.

We've alluded to it already: the horizon line of the inset picture extends to the left, runs around the edge of the painting to become the outline of the pointing finger; that finger then points into the circle of thick paint, a circle covered at one edge by a pile of vertical stretcher bars and crossed, top-to-bottom by a stripe of white paint laid down by a roller that, rolling over – and thereby revealing – a sequence of raised surfaces, crosses the horizon line of the inset picture from which we began.

There are three main spaces of the painting traversed in this description: (1) the inset picture, which depicts, according to mathematical perspective, an arched and circular structure in extended space, (2) the pointing figure, flat in comparison, which holds a manuscript with the symbols of an arch and circle, and (3) the circle of paint and the stretcher bars, two of which meet at a point, whose space is the space of the very materials used in (1) and (2).

If I'm right to see spaces (1) and (2) as representing, not just two spaces, but two ways of conceiving painting – as, roughly, the representation of illusionistic, extended space on the one hand, and the symbolization of an ideal or spiritual beyond on the other – then it is a small step to see space (3) as a conception of painting as abstract painting. I won't import more into these concepts than the fact that they are (or could be seen to be) parts of painting's history and modes of painting and thinking about painting's representational aims. Characterized by Gregor in this painting, the illusionistic mode uses foreshortened surfaces to represent the deep space of experience; whereas neither the symbolic nor abstract mode does. The depth of symbolic painting is not so much seen as thought. In it we are to encounter what it represents in a different sense – that is, what it stands for. Abstract painting is a misnomer: it is as concrete as paint gets. It presents the real depth of the material both illusionistic and symbolic painters used, and in Gregor's hands represents that material by depicting itself (painted paint, for instance).

Is there a sequence here? The finger points clockwise; the horizon line leaves to the left. I accept that I approach the brink of speculation to make the following reading. I read a sequence between these spaces and conceptions of painting in the order I listed them: (1) illusionistic, seen space leading to (2) symbolic (iconic) flat but suggestive space, thence to (3) the space of materials – canvas taut on stretcher bars and paint on it, which then shows (1) and (2) to have been this all along.

It will be observed to me that this is not the course of painting's history. Icon painting precedes linear perspective, associated with the Renaissance, and this latter tradition gave rise to the modernist plot arc that culminated in abstraction. But the significance of this sequence needn't be that of art history books. It may be, as I think it is, the sequence of modes that a painter might pass through. (Right about here is the cliff into speculation.) Seeing the world as extended, posing few visual problems – cameras and illustrations and eyes making linear space normal – one is naturally compelled to depict it as one finds it. But, wanting to show something beyond the visible world – beyond what cameras can capture – one turns to the less frequented rooms of the museum, to the icon painters, for whom realistic depiction was not the goal. But – and I'm bringing a lot, perhaps too much, to bear on that outstretched finger – all that the icons of the past seem to point to, to one not initiated into their faith and symbol systems, are the materials of painting and the very idea of pointing. Like the one in the world who wonders about getting out, the painter turning to these paintings finds no assurance of a beyond. From them one turns to those who took the materials of paint for what they are in this world. (The connection abstract painters saw themselves to have to icon painters might support one taking this step.) This is not the course of art history, but the course of one through it.

But where does it leave us? Gregor is not an abstract painter – Medium is not an abstract painting. Rather, it is a painting whose materials and history – which is the history of a painter moving through the possibilities history offers – have become its subject matter. Gregor, in this painting, does not make paint represent extended space or represent something beyond itself or represent the materials of painting – or, better: she does all of these, but none of them merely – but instead pursues a further conception of painting that represents conceptions of painting. We have to imagine that the three modes of painting depicted are none of them individually ways forward, but their interrelation is.

To ask the question which we were unprepared to ask before: what is this painting's conception of painting? I advance the following reading: painting, for Medium, is a form composed of the interrelation of parts in search of a satisfactory mode of representation. Among its parts are included its materials, what those materials represent, and the representational ends those materials have been put to in the past, which serve as possibilities for future painting and thinking about painting.

*****

Let's look at one more in some detail.

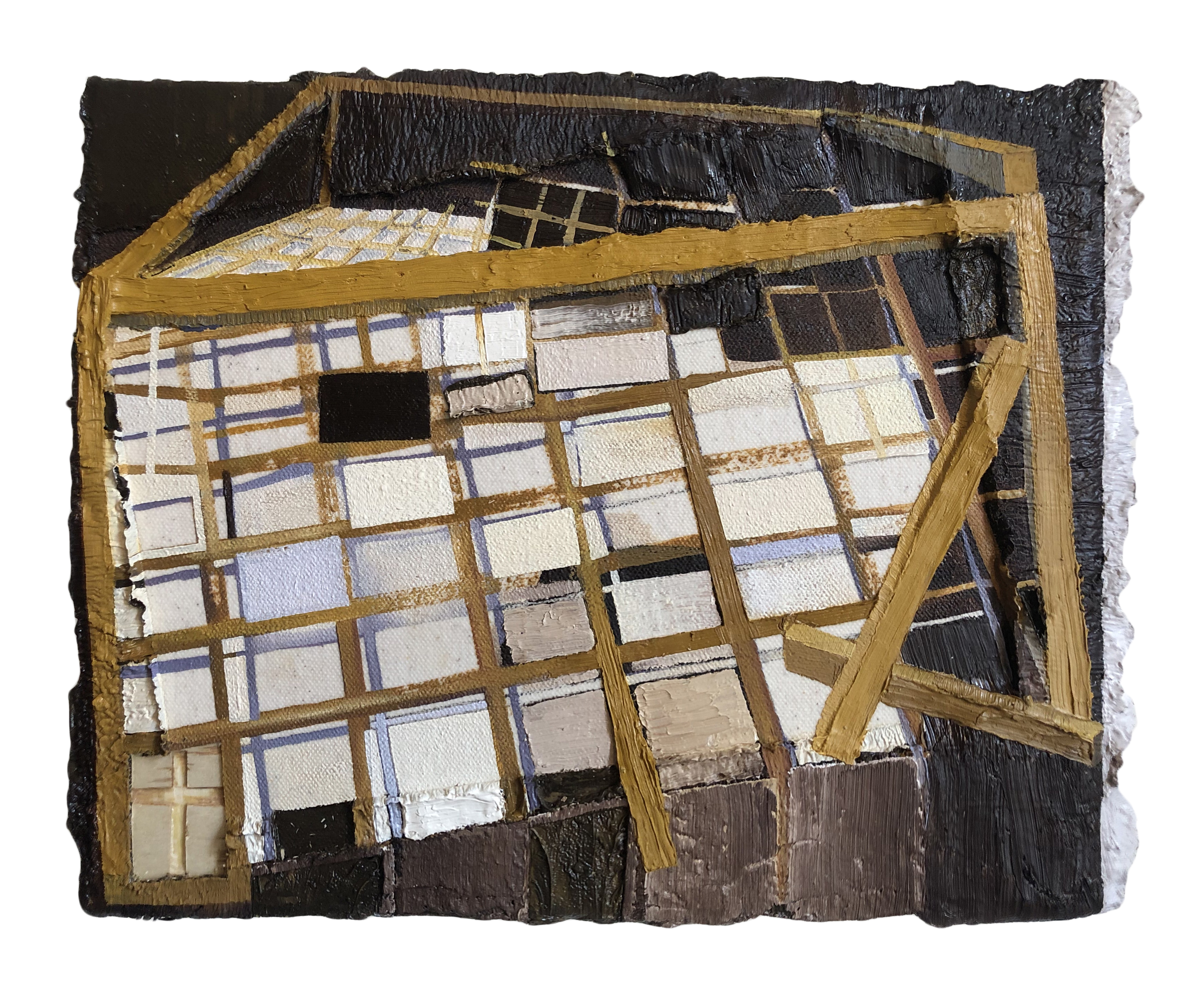

Trying to take in the space of Insulation at once is stifling. It looks like one room but the information we get conflicts. We make progress toward entering it when we notice it's divided roughly in half, top and bottom. The bottom half is depicted, as we've noticed, in reverse perspective: we look down from above, through rafters into a room. The top half is depicted in linear perspective, and taking the top by itself, we would say we were looking up from inside a room at the rafters.

We make more sense still of the room we're looking into and out of when we see it as a room under construction: plywood panels are in the process of being put up after insulating (incompletely) the walls; some are up already, and one leans against the far wall ready to be installed. While we're looking at it, notice the material and technical diversity of that panel of plywood. It is rendered in at least four different ways: by paint applied, by hatching scrapes into paint, by graphite that continues the hatching pattern, and by scraped away wood from the support itself to reveal textures of real wood; and these overlap with one another creating a gradient between means. This material diversity of objects goes for the beams of the rafters as well: here rendered by an under-layer of brown paint, there by purple scraped away to make grains, and elsewhere by graphite barely continuous with the lines beside it.

As we've had occasion to reflect on, one isn't sure whether they are in this space or out of it, nor whether there is a way between in and out. Is the tall rectangle at the far end of the room, for instance, a door or another panel of plywood? That is, a way out or a wall? There are two windows, both boarded – barely – by two planks. This is familiar from an overview of themes of Gregor's work. But now let us ask for specifics. What is this space?

Look at the windows: one at the bottom, nearest us, and one on the far wall, both closed by crossing boards. We might think by the way it's bordered that that far window was a mirror, reflecting the boarded up window closer to us. This would be a welcome discovery, for it would relate the top and bottom of the painting and suggest that this is one room and not two. But if we compare the slants of the boards in both we get the opposite tilt we'd expect from reflection. No, this is not a mirror; not a reflection. But there obviously is a likeness of form: two windows boarded up with the same upside-down cross shape.

The entire painting flips when we see that it is the very same window, depicted once from without and once from within. The two views this painting gives us, roughly divided into the top and bottom halves, are not just two views of the same room, but really two views of the same side of the room: the same wall: the same window; from within and from without. It is striking to consider and watch the central beam that runs up the middle of the painting: it is painted as one form – the only that plays a structural role in both views of the painting – which, in the lower half, runs up and away from us, until it, in the upper half, foreshortens toward us – this single visual form that represents the same beam viewed both from above and below.

What I'm describing is the best example yet of a view that can't be seen so much as thought. To make a connection with our analysis of Medium, it wields – in ways no icon painter has – the representational mode of icon painting we called symbolic. If we see a nod to Christian symbology in the crossing boards of the window, then in Insulation the cross, symbol of death and life after death – of a metaphysical promise of a beyond – has been flipped and become the physical barrier to escape. While wielding the language and techniques of some Christian painting, Gregor denies – or: doubts – though perhaps still desires – the life after life, beyond embodiment, that those icons whisper of. Gregor creates an impossible view that both traps us and keeps us out. But as was mentioned in passing about Escape Attempt, we seem – or certainly: the painter seems – complicit in maintaining this fact. We – or whoever's installing these panels – are constructing this room we trap ourselves in, insulating it from whatever lies outside. If Gregor's paintings seek to represent something beyond themselves they just as much barricade themselves against it. Or: the urge to flee is matched by an urge to stay – as if either urge unchecked by the other threatens to thwart their purpose. In their contradictory urges to leave and remain – in the room, in the world, in painting's history – we might read anxiety or despair, but we might also take courage from the rigor with which they face the problem that appears basic to their existence – and indeed seems basic to existence itself – namely, the fact that they – that we – are embodied.

*****

I will attempt no final synthesis of Gregor's way of seeing things. We have seen enough to know that there is a style and a taste here, along with a host of persistent questions and concerns continuous between these works – and that they are actively looking for ways forward for painting, and therefore, for living – or vice versa. It would be imprudent for this critic, writing of a living painter so clearly in the first lights of a dawning oeuvre, to record much more than the impressions and thoughts of a contemporary as excited for the next as for the present works. For I'm glad to share the world with them.